For those of you just hopping in, let me real quick explain what I am going to be doing the next couple weeks. I’ve started a mini-series analyzing the role of princesses (and inherently princes as well) in our society. I am pulling apart these “monumental” figures in the lives of millions of children across America. Instead of holding our children to the expectations of princes and princesses, it is my goal to create a more open environment for children to be independent, ambitious, and realistic.

To begin, for this week, it is important to lie a bit of foundation. Since these Fairy Tales are so popular in molding how our children conceptualize the ideal life, let’s see who the role models are for our princesses themselves. In the timeline below, the history of princesses and the original developments of their story are plotted. Notice the trend of where the majority of these princesses stem from. It appears that the one sided role models of our children’s lives were also constructed from one-sided role models of their time.

As you can see, except for the handful of outliers, the majority of the original tales of the princesses came from the Georgian and Victorian Eras (1714-1901). There is a lot that can be said about this, but the main thing is the women’s culture during these years.

As you can see, except for the handful of outliers, the majority of the original tales of the princesses came from the Georgian and Victorian Eras (1714-1901). There is a lot that can be said about this, but the main thing is the women’s culture during these years.

What did they look like? Women in this time only came in two types: fair white skin and everybody else. In The Body Project by Joan Jacobs Brumberg, she studies the intimate history of girls ranging from the 19th century to present day including insight on female maturation and expectation. Her key details of the ideal woman, as she noted from enormous data collection, were found to be as one sided as many of the princesses deriving from this era as well. Not only was the woman expected to be white, but also she was expected to be fair skinned. Everyone, from peasants to physicians, likened a pale woman to purity and innocence. This woman was thought to be rich enough that she did not have to leave the house in order to do work. This meant that she had other people below her doing the work so she could just lie around being “ladylike,” I suppose. Similarly, it was popular for a woman not to eat food in order to get a “skin and bones” body to show she was too weak to do any real work. If any pale woman were to go outside, she would take extra measures to make sure her skin was protected from harmful elements such as dirt, scratches, and the sun. On the other hand, women of any other color were seen as workers. By being a worker, it also reflected poor living standards and often times illness due to more exposure to, well, life. Physicians of the time even labeled colored women as unsanitary and unhealthy. These colored women had strong, working bodies with healthy dieting practices and immune systems. In this era, the fairer the woman, the better.

What did they act like? In this time, the most important thing a woman could do to prepare for marriage was to remain pure. Women were expected to be “ripe” (as they called it) at the time of marriage. She was to belong to her husband and nobody else. Men, on the other hand, were allowed to sleep with other women until marriage. In fact, there were even red light districts and other forms of prostitution in this era to allow men to have sex with other women. Purity for men was not held to the same standards as purity for women. Unfortunately, sexual diseases also began gaining momentum during this time, especially syphilis. Women would catch these diseases from their husbands, permanently damaging any form of purity she may have had, regardless of if she contracted it herself or not. To make matters worse, these women would then normally die in their mid-40s from the infection.

Furthermore, women were expected to be the moral compass of the family. In this way, she gained some sort of leverage in the marriage. If a woman questioned the morality of an event or occurrence, then the husband would have to listen to her. Although ultimately, he gets the last say, he will still (if he is a typical “gentleman” of the time) take her opinion into account.

In addition to these major things, women were also expected to behave quietly and simplistically. They were obedient and poise. They were levelheaded and punctual. If a family were like a tree during this era, then the man would be the roots of the family. Ultimately, he gets the say in where they will plot their life, what comes in or out, and how the source of income and power will impact the family. However, the woman would be like the trunk. She harbors the branches and controls the strength and direction they may take. She is in charge of sharing the wealth the roots bring in to the branches as well as protecting them. Although branches may fall, the trunk will hold firm. Branches, in terms of the 18th and 19th century lives, were the children and different assets a family has.

In this era, it is key, that above all else, the woman leads a sexually and spiritually pure life.

What did they do? At home, women were expected to pursue “accomplishments” such as embroidery and sewing, cooking, cleaning, and musical talent. It was discouraged to chase academic skills. Sometimes, a woman’s writing would be published, but this would normally happen after she had died as a way to show her purity and the tragedy of losing such a soul. If a woman’s writing was published in her lifetime, she was often deeply humiliated and would even possibly write an apology at the beginning of her work explaining how she didn’t want to publish it, but she was forced to.

As you could assume from above, there weren’t too many options for women to do occupationally. Most women were expected to stay in the home. Their daily chores included maintaining the house, caring for children, and when the husband came home, attending to his needs. On the rare occasion, a woman may go to work. These women were normally unmarried or widows. Their jobs reflected as an extension to the work they would complete in their own home: domestic servant and cleaning, and child rearing in the form of being a teacher. Once the telephone and typewriter were invented, women would sometimes work as a secretary of sorts for a man.

Although it wasn’t common, women in this era did grow to become professionals. Laura Bassi became an astronomy professor (1732), Maria Agnesi was a famous mathematician, Emilie du Chatelet was a physicist. The first female dentist was Lillian Lindsay in 1895 and the first female architect was Ethel Charles in 1898.

It’s not difficult to see how these harsh expectations of women and the lack of diversity transmitted into the popular fairy tale literature of the time. Disney princesses often have pale skin, light colored hair, frail and thin bodies, and little occupational skill. They are pure, and though they may teach children great moral standards, they do very little work outside of maintaining the home or completing domestic work.

So what?

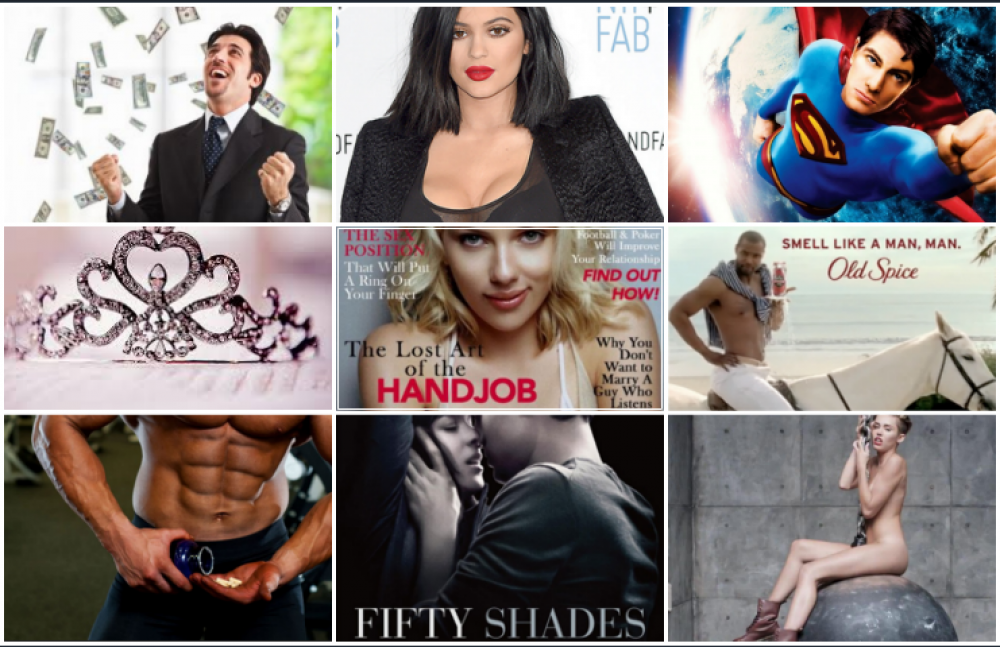

The times, they are a changin’. Although this may not be true in every country in the world, women are leaving the house. Since the 20th century, there have been countless improvements to the woman’s everyday life. Women are receiving educations, they are attaining successful careers, and they are exploring new fields of math and science right alongside men. Two hundred years ago, this would be appalling. However, things are still hard for women. Equality between genders is still more than an arm’s stretch away. One way to move women closer towards this end goal is to dismiss the assumption that our girls want to be like these princesses from the 18th and 19th centuries. It’s crucial to stop limiting girls in this way.

We no longer live in a nation where it is O.K. to be only one type of girl. Racial diversity, distinct physical body types, varied spiritual, intellectual, and personal pursuits, and individuality have become inevitable (and prosperous) characteristics of a beautifully progressive world. Don’t get hinged on the idea of a sort of monogamous relationship with girls and the world. There is much more to be seen of women and fairy tales just don’t capture that whole vision.

Check out the sources I used if you’d like:

A BBC article, Ideals of Womanhood in Victorian Britain

Occupations of women throughout history, A History of Women’s Jobs

Joan Jacobs Brumberg’s Novel, The Body Project

If you’re bored, you can take this little quiz that puts you in the position of an 18th century woman. It asks you questions and determines how you would fend off. In addition, it gives you historical notes about women in this era.

Read the complete stories by the Brothers Grimm here

Read the complete stories by Hans Christian Anderson here. Be warned, he can be very violently graphic. You can also read a little bit of history about him on this site as well.

I loved the background of the fairy tales in your post. It’s really cool to learn about the history behind them. That being said, I’m very glad we’ve left history in the past, and that society has progressed. I look forward to seeing more of your posts about this!

– Nora

LikeLike

I love that you’re taking the time to look into the idea of a princess and the cultural implications of what went into them, and how even though the ideal is defunct, it still affects perceptions of women in modern society! A lot of research went into this, and it’s super informative. But as Nora said, I’m glad we’ve, at least in part, managed to move past this more blatant manifestation of misogyny.

LikeLike

This is a super in-depth and well-researched post, nicely done! I think it’s interesting how you talk about the double-standards when it comes to sexual “purity.” Growing up homeschooled, I am unfortunately very familiar with the whole construct of “purity.” Among the religious right, many now claim that abstinence before marriage is just as important for men as it is for women, but this hardly seems to be the case: Where are the mother-son “purity balls”? Why aren’t daughters expected to consult a potential suitor’s mother to get “permission” to “court” him? No matter how much they deny it, these medieval ideals are still present. (I just noticed how many quotation marks I’m using. That alone probably gives a good indication of my feeling on the matter—haha.)

Anyways, enough about that. The timeline you provided is super fascinating! I definitely was not aware of the origins of some of these stories. (Mulan started out as a poem? Whaat?) I wonder how much these original stories were changed to make them more kid-friendly. I know the Grimm’s Tales can be rather, well, grim.

LikeLike